Sunday, November 27, 2005

Sleepless in Sudan

Via Kristof's column today, I found a blog by an aid worker in Darfur, who is giving uncensored information from Sudan and who, for fear of being kicked out of the country, is remaining anonymous.

In case you can't access the Kristof article, he's not really saying anything new: the African Union peacekeepers don't have enough people, money or matériel; the US isn't doing anything; things are getting worse, not better.

But at least Kristof keeps writing about Darfur. He may, at times, sound like a slightly annoying record that keeps skipping, particularly if you listen to the multimedia pieces on the Times website, but he is one of the only people from a large American media outlet who has been struggling to keep Darfur ingrained in his public's fickle short-term memory. And for that, he deserves respect.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Rigged Guantanamo Bay military commissions

I just received a package from my family with some Christmas presents and the last three months of Harper's. There was a "reading" in there that I had never heard about. It is an exerpt from a March 2004 email in which Air Force Captain John Carr, one of the military prosecuters in the cases at Guantanamo Bay who has since then been transferred, complained to Army Colonel Fred Borch about the way the Office of Military Commissions was being carried out.

The Australian Broadcast Service seems to be the first to report that the trials were to be rigged.

I can't seem to find a transcript of the email on the internet, so I'm retyping the exerpt published in the November issue of Harper's (emphasis mine):

Sir,According to the ABC article, prosecutor Major Robert Preston feels the same way: "After all, writing a motion saying that the process will be full and fair when you don't really believe it is kind of hard, particularly when you want to call yourself an officer and lawyer."

I feel a responsibility to emphasize a few issues. Our cases are not even close to being adequately investigated or prepared for trial. There are many reasons why we find ourselves in this unfortunate position--the starkest being that we have had little or no leadership or direction for the last eight months. It appears that instead of pausing, conducting an honest appraisal of our current preparation plan for the future, we have invested substantial time and effort in concealing our deficiencies and misleading not only each other but also those outside our office who are either directly responsible for or asked to endorse our efforts. My fears are not insignificant that the inadequate preparation of the cases and misrepresentation related thereto may constitute dereliction of duty, false official statements, and other criminal conduct.

You asked in our meeting last week what else you could do but lead by example. In regards to the environment of secrecy, deceit, and dishonesty in this office, the attorneys appear merely to be following the example that you have set.

A few examples include:

You continue to make statements to the office that you admit in private are not true. You have stated for months that we are ready to go immediately with the first four cases. At the same time, emails are being sent out admitting that we don't have the evidence to prove the general conspiracy, let alone the specific accused's culpability.

You have repeatedly said to the office that the military panel will be handpicked and will not acquit these detainees, and we only needed to worry about building a record for the review panel. In private you stated that we are really concerned with review by academicians ten years from now, who will go back and pick the cases apart.

The fact that we did not approach the FBI for assistance prior to December 17 is not only indefensible but an example of how this office and others have misled outsiders by pretending that interagency cooperation has been alive and well for some time, when in fact the opposite is true.

It is my opinion that the primary objective of the office has been the advancement of the process for personal motivations--not the proper preparation of cases or the interests of the American people. The posturing of our prosecution team chiefs to maneuver onto the first case is overshadowed only by the zeal with which they hide the specific facts of their case from review or scrutiny. The evidence does not indicate that our military and civilian leaders have been accurately informed of the state of our preparation, the true culpability of our accused, or the sustainability of our efforts.

If the appropriate decision-makers are provided with the accurate information and determine that we must go forward on our current path, then all would be very committed to accomplishing this task. It instead appears, however, that the decision-makers are being provided false information to get them to make the key decisions, only to learn the truth after a point of no return.

When I volunteered to assist with this process, I expected there would at least be a minimal effort to establish a fair process and diligently prepare cases against significant accused. Instead, I find a half-hearted and disorganized effort by a skeleton group of relatively inexperienced attorneys to prosecute fairly low-level accused in a process that appears to be rigged. It is difficult to believe that the White House has approved this situation, and I fully expect that one day, soon, someone will be called to answer for what our office has been doing for the last fourteen months.

While many may simply be concerned with a moment of fame and the ability in the future to engage in small-time practice, that is neither what I aspire to do not what I have been trained to do. I cannot morally, ethically, or professionally continue to be a part of this process.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Padilla's indictment

Jose Padilla, an American citizen, was finally indicted yesterday in a criminal court. Padilla, who has been held as an "unlawful enemy combatant" in a Navy brig in South Carolina since 2002, was arrested in Chicago and accused of planning a "dirty bomb" attack on American soil. His indictment makes no mention of a "dirty bomb," perhaps because any evidence gained while he was detained without recourse to a writ of habeas corpus would be inadmissable in court.

According to I. Michael Greenberger, a former Justice Department official who teaches law at the University of Maryland,

The indictment is doubtless a strategy by the Bush administration to avoid a Supreme Court ruling that would likely hold that U.S. citizens cannot be detained incommunicado as enemy combatants if they are detained on U.S. soil.The US government had until today to turn in its legal arguments for a pending Supreme Court case, which was to examine Padilla's status. Attorney General Gonzales claims, "Since he has now been charged in a grand jury in Florida, we believe that the petition is moot and that the petition should not be granted." But this is not at all certain, since the change to the US criminal court system did not address his status as an "unlawful enemy combatant," (a designation that is being used to hold other people indefinitely) and in a government request in 2002 to suspend a petition to habeas corpus, government lawyers make the following claim in a footnote:

There has never been an obligation under the laws and customs of war to charge an enemy combatant with an offense (whether under the laws of war or under domestic law). Indeed, in the usual case, the vast majority of those seized in war are never charged with an offense but are simply detained during the conflict. Nor is there any general right of access to counsel for enemy combatants under the laws and customs of war.This implies that the government is talking about the "war on terror" and not the war in Afghanistan, because if they were talking about the latter, Padilla would have been released before now. Needless to say, this is disconcerting, because if the "war on terror" were to last as long as another metaphorical war, say the "war on drugs," the "unlawful enemy combatant" designation would give the president the power to imprison anyone, even US citizens, for the rest of their lives without having to ever charge them with a crime.

As a matter of fact, the Supreme Court decision handed down by O'Conner in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (Hamdi is an American citizen who was apprehended in Afghanistan during the war there) explicitly makes this point:

Hamdi objects, nevertheless, that Congress has not authorized the indefinite detention to which he is now subject. The Government responds that "the detention of enemy combatants during World War II was just as 'indefinite' while that war was being fought." Id., at 16. We take Hamdi's objection to be not to the lack of certainty regarding the date on which the conflict will end, but to the substantial prospect of perpetual detention. We recognize that the national security underpinnings of the "war on terror," although crucially important, are broad and malleable. As the Government concedes, "given its unconventional nature, the current conflict is unlikely to end with a formal cease-fire agreement." Ibid. The prospect Hamdi raises is therefore not far-fetched. If the Government does not consider this unconventional war won for two generations, and if it maintains during that time that Hamdi might, if released, rejoin forces fighting against the United States, then the position it has taken throughout the litigation of this case suggests that Hamdi's detention could last for the rest of his life.O'Conner then goes on to speak of the "constitutional balance" needed when weighing freedom and security:

Striking the proper constitutional balance here is of great importance to the Nation during this period of ongoing combat. But it is equally vital that our calculus not give short shrift to the values that this country holds dear or to the privilege that is American citizenship. It is during our most challenging and uncertain moments that our Nation's commitment to due process is most severely tested; and it is in those times that we must preserve our commitment at home to the principles for which we fight abroad. See Kennedy v. Mendoza&nbhyph;Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 164?165 (1963) ("The imperative necessity for safeguarding these rights to procedural due process under the gravest of emergencies has existed throughout our constitutional history, for it is then, under the pressing exigencies of crisis, that there is the greatest temptation to dispense with guarantees which, it is feared, will inhibit government action"); see also United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258, 264 (1967) ("It would indeed be ironic if, in the name of national defense, we would sanction the subversion of one of those liberties ... which makes the defense of the Nation worthwhile").I've talked about this idea on a few occasions (here and here), and the prospect of an executive branch that has the power to indefinitely detain its citizens is indeed a frightening one. This is why it is important that the Supreme Court go ahead and hear the case, instead of letting the government cop out at the last minute. This is not unexpected, however, since rather than actually try Hamdi, the government agreed to let him go back to Saudi Arabia on the condition that he give up his American nationality.

So the government's behavior in both of these cases is not only unconstitutional and contrary to the tule of law in general, it seems contradictory and counterproductive. If Padilla was really trying to build a "dirty bomb," the prosecuter in his case cannot make that claim due to his unlawful detention. Likewise, if Hamdi is so dangerous, why let him go back to Saudi Arabia (of all places!) rather than give him a fair criminal trial? It's important that the Supreme Court hear Padilla's case regardless of the government's last minute cop-out, if only to stress Justice O'Connor's assertion that "...a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation's citizens."

Monday, November 21, 2005

The Salvador option

Last night, I began reading Mark Danner's book, The Massacre at El Mozote , which descibes the brutal murder of hundreds of people in a sacristy in a small Salvadoran village by American-backed government forces fighting a dirty war against leftist rebels. As coincidence would have it, I saw (via Christopher Dickey's blog) that the Salvadoran former colonel, Nicolas Carranza, had been found responsible for crimes against humanity in a court in Memphis. Carranza, who moved to Memphis in 1985 and then became an American citizen, was the Vice Minister of Defense in El Salvador from 1979 to 1981 and then head of the Treasury Police in 1983. The latter was reputed to be the most violent of the country's security forces.

For more information on the Salvadoran civil war, see the report by the Truth Commission.

The massacre in El Mozote is interesting to me in and of itself, but it does have some relevance to the situation in Iraq. Earlier this year, Christopher Dickey briefly explored the prospect of employing the "Salvador Option" in Iraq. Presumably, these dirty war tactics would entail not only assassination and kidnapping, but also torture. The recent discovery of the Iraqi Interior Ministry's secret interrogation center -- where many Sunnis were apparently tortured, perhaps by members of the Shia paramilitary forces of the Sadr Brigade, who have reportedly become deeply embedded in the Ministry -- should bring up questions about torture carried out by the US and its allies in Iraq.

We have known for a long time what US proxy forces did in Central America, so why should we be suprised when the same thing happens in Iraq, particularly since the Bush administration was reported to have been debating the "Salvador option" only 10 months ago?

In any case, those who are committing torture in Iraq, be they American or Iraqi, should take note of Carranza's trial, because, as Hissène Habré and Joseph Kony will find out soon enough, they are not above the law.

On standing down

Last week, Vietnam veteran and Pennsylvania Congressman Murtha, who is the ranking member of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense, gave a speech in which he outlined the reasoning behind his proposed motion to redeploy all American forces out of Iraq "at the earliest praticable date..." maintaining "a quick-reaction U.S. force and an over-the-horizon presence of U.S. Marines...in the region."

The reasons he gives, which are stated in his proposal, are as follows:

...Congress and the American People have not been shown clear, measurable progress toward establishment of stable and improving security in Iraq or of a stable and improving economy in Iraq, both of which are essential to "promote the emergence of a democratic government";I won't even go into the Republican response to his motion, which was childish and counterproductive, but probably smart politics; however, Murtha's reasoning deserves to be looked at honestly.

...additional stabilization in Iraq by U, S. military forces cannot be achieved without the deployment of hundreds of thousands of additional U S. troops, which in turn cannot be achieved without a military draft;

...more than $277 billion has been appropriated by the United States Congress to prosecute U.S. military action in Iraq and Afghanistan;

...as of the drafting of this resolution, 2,079 U.S. troops have been killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom;

...U.S. forces have become the target of the insurgency,

...according to recent polls, over 80% of the Iraqi people want U.S. forces out of Iraq;

...polls also indicate that 45% of the Iraqi people feel that the attacks on U.S. forces are justified;

...due to the foregoing, Congress finds it evident that continuing U.S. military action in Iraq is not in the best interests of the United States of America, the people of Iraq, or the Persian Gulf Region, which were cited in Public Law 107-243 as justification for undertaking such action;

It has long been argued that a premature withdrawal of American troops would lead to an all out civil war in Iraq. It is hard to say, however, how accurate this idea is. It is entirely possible that the only thing holding the Iraqi people together is a common enemy: the Americans. (I am immediately reminded of the Syrian forces that stopped the war in Lebanon and then subsequently occupied the country for a decade and a half, as well as the comment made to me by a Palestinian born and raised in Lebanon, who said she hoped the Syrians wouls stay, because she didn't want another civil war to break out.) However, there is also the distinct possibility that Murtha is correct and US forces are the destabilizing force in the region. If there were no coalition forces to resist, there would be no need for a nationalist Iraqi insurgency, and those who continued to fight the Iraqi government would be seen as sectarian belligerents or religious zealots instead of nationalist freedom fighters.

But I'm not really sure that that's the real question we should be looking at. The important question is that of security versus democracy. If what we are really interested in is Iraqi stability, then we should have left Saddam Hussein in charge. But we purport to be interested in more than just security; the post-invasion rhetoric has been largely about liberating Iraqis and fostering democracy in the Middle East. Granted, there is a certain moral responsiblity inherent in the pottery barn motto of "you break it, you bought it," which would suggest that we have an obligation to clean up the mess we made. But there comes a time when even if it is our fault, we have to ask ourselves if we are only making matters worse by trying to clean up our mess.

And besides, to go back to the idea of democracy, if Iraq is, in fact, a sovereign nation, that decision is not really ours to make in the first place. To my mind, there ought to be a national referendum during the December elections that asks each Iraqi voter, "should the coalition forces withdraw from Iraq?" If the answer is "yes," then we should respect the Iraqi people's wishes and withdraw as soon as possible. However, we should still offer to train Iraqi police and military forces in addition to teachers, engineers, and anyone else needed to help rebuild Iraq's demolished infrastructure. This could be in somewhere like Kuwait or Qatar.

In the end, perhaps we should stand down, so the Iraqis can stand up.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Guantanamo Bay and habeas corpus

In order to understand the motions to be voted on later today about habeas corpus rights for detainees at Guantanamo Bay, it is useful to step back, with the help of Human Rights Watch's overview, and review the whole process in motion there.

President Bush declared in November 2001 that non-US citizens accused of terrorism could be tried by an ad-hoc military commission, instead of by a court martial or a federal civilian court. The justification was that the people being detained were not prisoners of war, but rather "enemy combatants," who have no rights under the Geneva Conventions. There are about 550 people being detained at Guantanamo Bay, detained sometimes by US forces, sometimes by foreign services or turned over to the US by the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan in exchange for a $5,000 bounty. Some have been released, mostly because of deals with their home governments, who have expressed dissatisfaction with the proposed ad-hoc military commissions. The British Attorny-General described them as "not ... the type of process which we would afford British nationals."

The purpose of military commissions is to try non-US citizens who are charged with having participated in international terrorism against the United States. Authorized in November 2001, their panels are made up of 3-7 members, all of whom must be current or retired members of the US military and only one of which must have a law degree. The detainee must be assigned military defense council, but can hire a civilian lawyer at his own expense. According to HRW,

The normal rules of procedure in a court martial do not apply in the military commissions. Hearsay evidence can be admissible. Decisions are based on a majority of commission members, except in death penalty cases, where a unanimous verdict is required. Cases are reviewed by a military review panel, but there is no appeal to a civilian court as is the case with courts martial. Final review rests with either the Secretary of Defense or the President.To date, only 4 detainees have been formally charged with offences in odrer to be tried in a military commission.

In the meantime, while many detainees will begin their 5th year of detention at Guantanamo Bay this year, the Department of Defense has set up these tribunals for detainees to challenge their status as a "enemy combatants." They were introduced in response to the supreme court decision in Rasul v. Bush, in which the Court ruled that federal courts had the jurisdiction to hear claims made by Guantanamo detainees challenging their imprisonment.

Each detainee is assigned a "personal representative," who is a military officer and not a lawyer, to assist him in the process. He then appears before 3 military officers, who decide whether or not he has been correctly labeled as an "enemy combatant."

According to the Washington Post, the DOD has stated that 558 Tribunals have taken place. Of these, the tribunal have decided on 509 cases, of which 33 detainees were found not to be "enemy combatants," but only 4 have been released. The same article, takes a look at the first case in which classified evidence used in the tribunal has become public.

The case, decided in 2004, is about Murat Kurnaz, a German citizen of Turkish descent, who was seized in Pakistan in 2001. According to the Tribunal, Kurnaz was a member of al Qaida and an "enemy combatant" and as such, could be detained indefinitely in Guantanamo Bay. This is what was found:

In Kurnaz's case, a tribunal panel made up of an Air Force colonel and lieutenant colonel and a Navy lieutenant commander concluded that he was an al Qaeda member, based on "some evidence" that was classified.So to summarize, the one case in which we have the evidence used to decide whether someone was an "enemy combatant" shows that the process is a show trial and fundamentally unfair. Both the German government and the US Command Intelligence Task Force found that Kurnaz was innocent, but 3 US military officers decided otherwise. So an innocent man has been languishing in prison, where he has most likely been abused and tortured for 4 years.

But in nearly 100 pages of documents, now declassified by the government, U.S. military investigators and German law enforcement authorities said they had no such evidence. The Command Intelligence Task Force, the investigative arm of the U.S. Southern Command, which oversees the Guantanamo Bay facility, repeatedly suggested that it may have been a mistake to take Kurnaz off a bus of Islamic missionaries traveling through Pakistan in October 2001.

"CITF has no definite link/evidence of detainee having an association with Al Qaida or making any specific threat against the U.S.," one document says. "CITF is not aware of evidence that Kurnaz was or is a member of Al Quaeda."

Another newly declassified document reports that the "Germans confirmed this detainee has no connection to an al-Qaida cell in Germany."

Only one document in Kurnaz's file, a short memo written by an unidentified military official, concludes that the German Muslim of Turkish descent is an al Qaeda member. It says he was working with German terrorists and trying in the fall of 2001 to reach Afghanistan to help fight U.S. forces.

In recently declassified portions of her January [2005] ruling, [US District Judge Joyce Hens] Green wrote that the panel's decision appeared to be based on a single document, labeled "R-19." She said she found that to be one of the most troubling military abuses of due process among the many cases of Guantanamo detainees that she has reviewed.

The R-19 memo, she wrote, "fails to provide significant details to support its conclusory allegations, does not reveal the sources for its information and is contradicted by other evidence in the record." Green reviewed all the classified and unclassified evidence in the case.

So that is the context that we find ourselves in when the US Senate is trying to strip detainees of their right (decided on by the Supreme Court) to habeas corpus. To bring us back up to speed, there has been a "compromise" amendment to the original motion proposed by Senator Graham (R-SC) as well as a new version of the Bingaman amendment (D-NM). Thanks to Obsidian Wings, copies of those two amendments are available here and here (both are in pdf format).

The new "compromise" amendment states that if found guilty by a Military Commission and sentenced to the death penalty or 10 years or more in prison, the case would automatically be sent to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia or at the court's discretion for any other case. However, we must remember that since these people have been detained, only 4 have actually been charged with any offence. The rest are being held indefinitely without being charged, and it was for these cases that the Supreme Court said federal courts could hear habeas corpus cases.

As for the judicial review of the detention of enemy combatants, the new amendment still states,

No court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien outside the United States ... who is detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.It then goes on to state,

...the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit shall have exclusive jurisdiction to determine the validity of any decision ... that an alien is properly detained as an enemy combatant.The language of the competing Bingaman amendment, on the other hand, states that the court of appeals would have jurisdiction to consider an application for writ of habeas corpus, provided that the detainee has been subjected to a Combat Status Review Tribunal but is not yet charged with an offense before a military commission (the case of most of the detainees). There is, however, another exemption for any "individual not designated as an enemy combatant following a combatant status review, but who continues to be held by the United States Government." This would presumably include the 29 detainees who were found not to be "enemy combatants," but who have not been released yet.

Under the Bingaman amendment, the court could review the following things:

(A) whether the status determination of the Combatant Status Review Tribunal ... was consistent with the procedures and standards specified by the Secretary of Defense for Combatant Status Review Tribunals;However, in contrast to his first proposal, the new Bingaman amendment says that the appeals court may not "consider claims based on living conditions."

(B) whether such status determination was supported by sufficient evidence and reached in accordance with due process of law, provided that statements obtained through undue coercion, torture, or cruel or inhuman treatment may not be used as a basis for the determination; and

(C) the lawfulness of the detention of such alien.

To be honest, I don't quite understand the distinction made in the Graham amendment between the appeals court's jurisdiction to hear an application for a writ of habeas corpus and its jurisdiction to "determine the validity of any decision ... that an alien is properly detained as an enemy combatant." The only difference that I can tell would be that the former would seem to be reviewing the case from scratch (although this doesn't seem to be the case in the Bingaman amendment either), whereas the second would be reviewing the decision of another body based on the rules of that body, the criteria being much more stringent in a civilian court of appeals reviewing a writ of habeas corpus than the stated criteria of the Combatant Status Review Tribunals. This would seem correct from the Kurnaz case, which is the only example we have of these tribunals so far.

This certainly does seem to be a "compromise," but not necessarily in the good sense of the term. While better than the original motion, it still compromises the rule of law by letting flawed tribunals take the place of an experienced civil legal system or even military courts martial.

As for the Bingaman amendment, it seems less likely to pass, but is much better than the Graham amendment, particularly since it explicitly says that evidence gained from torture is off limits for deciding a detainees status, even if it does soften its stance on the living conditions of detainees. And one shouldn't mistake the question of living conditions with halal meat or air conditioning. Living conditions is a euphemism used to not say outright "whether or not detainees are being tortured."

For more information, there was an op-ed in the Times today, as well as an article in the Post on the subject today.

Monday, November 14, 2005

More on habeas corpus

Via Kevin Drum's Political Animal, Obsidian Wings have a pretty thorough 13-part account of the measure, which explains and debunks Lindsey Graham's rhetoric point by point.

There is also an amendment by NM Senator Bingaman (S. AMDT 2517 to bill S. 1042.), which would defeat the Graham amendment. I'm not sure exactly when it will be voted on (I think tomorrow), but you can use this site or this one to contact your senators to get them to vote for the Bingaman amendment.

Slouching away from the rule of law

Last week, the American Senate voted 49 to 42 to strip detained "enemy combattants" in Guantanamo Bay of their right to habeas corpus, which was won in the 2004 Supreme Court case of Rasul v. Bush decision. That decsision found that federal courts had the jurisdiciton to hear the detainees' cases when suing for habeas corpus. Justice Stevens delivered the Court's decision and quoted an 1953 opinion by Justice Jackson:

Executive imprisonment has been considered oppressive and lawless since John, at Runnymede, pledged that no free man should be imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, or exiled save by the judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. The judges of England developed the writ of habeas corpus largely to preserve these immunities from executive restraint.According to the Times, Senator Graham, who sponsored the measure, said that it is necessary, because the detainees' blizzard of legal claims was tying up the Department of Justice's resources.

This comes nearly 2 years after the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) published their report on the prisoners being held in Iraq, which stated that:

Certain CF [Coalition Forces] military intelligence officers told the ICRC that in their estimate between 70% and 90% of the persons deprived of their liberty in Iraq had been arrested by mistake.Of course, prisons in Iraq and Guantanamo Bay are not necessarily the same thing, although the US practice of offering bounties to Northern Alliance forces for bringing them supposed members of the Taliban gives us no real reason to suspect otherwise. This article in the Guardian gives us an idea of what is happening in Guantanamo Bay.

There are about 500 prisoners there, who have been held for almost 4 years without being charged with a crime. Of these, 200 have filed habeas corpus motions. One such person is Adel, represented pro bono by P. Sabin Willett, who writes in today's Washington Post that detainees deserve court trials:

Adel is innocent. I don't mean he claims to be. I mean the military says so. It held a secret tribunal and ruled that he is not al Qaeda, not Taliban, not a terrorist. The whole thing was a mistake: The Pentagon paid $5,000 to a bounty hunter, and it got taken.At a the Tehran Conference in 1943, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt discussed what to do with the Nazis after the war was over. Stalin, true to form, suggested that 50,000 or maybe even 100,000 nazis should be summarily executed instead of having any sort of a trial. Roosevelt did not seem entirely against the idea, but Churchill left the room in disgust. In the end, there was no mass killing of nazis; the Nuremburg trials were conducted instead. The decision between mass killings/mass imprisonment and the rule of law is what seperates civilized nations from uncivilized ones; the writ of habeas corpus is older than the American constitution and was later enshrined in that document.

The military people reached this conclusion, and they wrote it down on a memo, and then they classified the memo and Adel went from the hearing room back to his prison cell. He is a prisoner today, eight months later. And these facts would still be a secret but for one thing: habeas corpus.

Only habeas corpus got Adel a chance to tell a federal judge what had happened. Only habeas corpus revealed that it wasn't just Adel who was innocent -- it was Abu Bakker and Ahmet and Ayoub and Zakerjain and Sadiq -- all Guantanamo "terrorists" whom the military has found innocent.

It has become apparent that many people being held by the US are completely innoccent. Either the US is a civilized state governed by the rule of law and fair trials as its constitution would lead us to believe, or it decides to forfeit the very ideas of freedom and justice that the "war on terror" purports to be protecting. In the first case, the people being held indefinitely should have the chance to prove their innocence in a court of law. In the second, the US will have bridged much of the distance that seperates police states and democracies.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

Black sites and torture, again

Because I've been spending so much time on the riots here, I haven't put anyhting up on the recent discovery of CIA "black sites," which make up a system of covert prisons located at various times in 8 different coutries, including Afghanistan, Thailand, Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, Poland and Romania.

The story was first broken by the Washington Post, which declined to name the "several democracies in Eastern Europe" that have been accused of hosting these prisons, which would be illegal under US and international law, because of the torture techniques used there and the prisoner's lack of recourse to any legal system.

It is illegal for the government to hold prisoners in such isolation in secret prisons in the United States, which is why the CIA placed them overseas, according to several former and current intelligence officials and other U.S. government officials. Legal experts and intelligence officials said that the CIA's internment practices also would be considered illegal under the laws of several host countries, where detainees have rights to have a lawyer or to mount a defense against allegations of wrongdoing.According to the Post Article, the black sites are the highest level of the covert prison network, which includes a second tier for detainees deemed less important who are then "rendered" to other countries.

Host countries have signed the U.N. Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, as has the United States. Yet CIA interrogators in the overseas sites are permitted to use the CIA's approved "Enhanced Interrogation Techniques," some of which are prohibited by the U.N. convention and by U.S. military law. They include tactics such as "waterboarding," in which a prisoner is made to believe he or she is drowning.

More than 100 suspected terrorists have been sent by the CIA into the covert system, according to current and former U.S. intelligence officials and foreign sources. This figure, a rough estimate based on information from sources who said their knowledge of the numbers was incomplete, does not include prisoners picked up in Iraq.After this piece, the Financial Times picked up the ball and published the names of Romania and Poland as two of the eastern European coutries that have hosted covert CIA prisons. Poland was recently accepted into the EU and Romania is scheduled to become a member in 2007. Apparently, there has been a fair ammount of eastern European cooperation during the CIA practice of rendiditon, in which countries in the region allow the CIA to refuel and transfer prisoners in transit to Egypt, Saudia Arabia, Morocco, Uzbekistan, Syria and Jordan, where they are then "interrogated" by local intelligence agencies.

The detainees break down roughly into two classes, the sources said.

About 30 are considered major terrorism suspects and have been held under the highest level of secrecy at black sites financed by the CIA and managed by agency personnel, including those in Eastern Europe and elsewhere, according to current and former intelligence officers and two other U.S. government officials. Two locations in this category -- in Thailand and on the grounds of the military prison at Guantanamo Bay -- were closed in 2003 and 2004, respectively.

A second tier -- which these sources believe includes more than 70 detainees -- is a group considered less important, with less direct involvement in terrorism and having limited intelligence value. These prisoners, some of whom were originally taken to black sites, are delivered to intelligence services in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Afghanistan and other countries, a process sometimes known as "rendition." While the first-tier black sites are run by CIA officers, the jails in these countries are operated by the host nations, with CIA financial assistance and, sometimes, direction.

Morocco, Egypt and Jordan have said that they do not torture detainees, although years of State Department human rights reports accuse all three of chronic prisoner abuse.

The top 30 al Qaeda prisoners exist in complete isolation from the outside world. Kept in dark, sometimes underground cells, they have no recognized legal rights, and no one outside the CIA is allowed to talk with or even see them, or to otherwise verify their well-being, said current and former and U.S. and foreign government and intelligence officials.

All of this comes when Vice President Dick Cheney has been lobbying Congress to exempt the CIA from an explicit ban on torture proposed by Republican Senator John McCain, who was tortured as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Senator Jeff Sessions of Alabama, however, seemed to have been convinced by Cheney.

According to the Financial Times article, Deborah Pearlstein, director of the US law and security programme at Human Rights First, has attacked the VP's actions.

Ms Pearlstein attacked efforts by Dick Cheney, vice-president, to have the CIA exempted from legislation proposed by Senator John McCain that would reaffirm the illegality of cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment of prisoners held by the US.

The American Civil Liberties Union recently released details of autopsy and death reports it obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. It said 21 deaths were listed as homicides. Eight people appeared to have died during or after interrogation by Navy Seals, military intelligence and "OGA" ? Other Governmental Agency, which is commonly used to refer to the CIA.

Friday, November 11, 2005

The good, the bad and the ugly

Today I'd like to look at three very different ways of covering the riots in the French suburbs. I'll go in the order prescribed by Clint Eastwood.

On the more assuring side of the coverage of the riots, the New York Times published an op-ed piece by Olivier Roy from the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris. He is a specialist of Islamist movements as well as Central Asia, and while his conclusions are common sense to most people living here in Paris, they are desperately needed in the Anlgophone, and particularly the American, press (thanks to Josh for the link):

The rioting in Paris and other French cities has led to a lot of interpretations and comments, most of them irrelevant. Many see the violence as religiously motivated, the inevitable result of unchecked immigration from Muslim countries; for others the rioters are simply acting out of vengeance at being denied their cultural heritage or a fair share in French society. But the reality is that there is nothing particularly Muslim, or even French, about the violence. Rather, we are witnessing the temporary rising up of one small part of a Western underclass culture that reaches from Paris to London to Los Angeles and beyond. ...

Most of the rioters are from the second generation of immigrants, they have French citizenship, and they see themselves more as part of a modern Western urban subculture than of any Arab or African heritage.

Just look at the newspaper photographs: the young men wear the same hooded sweatshirts, listen to similar music and use slang in the same way as their counterparts in Los Angeles or Washington. (It is no accident that in French-dubbed versions of Hollywood films, African-American characters usually speak with the accent heard in the Paris banlieues). ...

In the end, we are dealing here with problems found by any culture in which inequities and cultural differences come in conflict with high ideals. Americans, for their part, should take little pleasure in France's agony - the struggle to integrate an angry underclass is one shared across the Western world.

On the bad side and in the blogosphere, I've run across a site called Oxblog, in which an Irish student, who came to Paris obstentibly to cover the riots, has decided to don a turtleneck and a leather jacket to blend into his surroundings:

As assiduously as I donned turtleneck and leather jacket to simulate a Frenchman and, it was hoped, a not too out of place banluisard [sic], I still perhaps didn't quite fit in, whatever diversified portfolio of national identities in which I might traffic, French maghrebian [sic] being decidedly not among them.I'm not not making this up. You can see the entry for yourself here. Somehow this guy has gotten on a Public Radio International show about blogging, called Open Source.

But before you reassure yourself by remembering that anyone can make a blog, it's worth taking a look at this Notre Dame and Yale graduate's bio, in which he explains his "current book projects." One of them is a book called "In the Way of the Prophet" and is about "Muslim communities in the United States, Britain, and France."

I'm not really sure whether to laugh or to cry. But then again, maybe this description is as inflated as his claim of being fluent in French: his latest blog entry begins with "ESCUSEZ MONSIEUR, JE CHERCHE RACAILLE," which ought to be "Excusez-moi, Monsieur, je cherche des racailles" but instead translates to something like, "Escuse sir, I look for gangsta."

Scanning through his posts will show you that according to him, these riots are the "the handiwork of determined criminal gangs," instead of teenagers who are turning their hate into the sport of burning things. He also reports that all of Paris is suffering from a sense of malaise, which I suspect has more to do with wanting to slip French words into his account that anything he's actually seen or heard here. Other mistakes include things like saying that somone has been "assaulting the Marais's Jews" and mentioning "postgraduate degree holders working as postmen," the latter of which makes me think that he has a weak spot for hyperbole and alliteration.

But say what you will about this guy, he certainly is ambitious, and I almost feel bad poking fun at him knowing that he was apparently mugged in Aulney-sous-Bois recently. But only almost. That last post's pun left me feeling fairly pitiless.

Finally, last night at a friend's birthday dinner, another friend told me about what she saw on le Zapping, a segment on the French cable channel, Canal +, which shows ridiculous, funny or just plain silly clips found that day on television. Yesterday's zapping shows American cable news coverage of the riots, in which CNN shows a map of France where Toulouse is in the Alps, Cannes is on the border of Spain and even Paris is not really in its correct place. They then cut to Bill O'Reilly of Fox News, who says that France deserves its "Muslim riots," mostly because they didn't support the US in the invasion of Iraq.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Foreigners in Paris

According to an article this morning in the free daily, Metro, Jean-Pierre Dupois, president of the League of Human Rights claimed that Sarkozy's proposition to deport all foreigners involved in the riots is "totally illegal, because it is a collective expulsion and this sort of expulsion is forbidden by the European Convention on Human Rights. Even as the Council of State is concerned, it is illegal."

In other news, the Parisian municipal government showed its support yesterday for a campaign called Tous Parisiens, tous citoyens (All Parisians, all citizens), which would give Paris's foreigners (14% of the local population) the right to vote in local elections. As a foreigner living in Paris for five years now, I have to say that this decision would be more than welcome.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

More on the riots

First off, I'm glad to see that there is someone in the US who actually has a fairly good idea of what's happening here now. It's not surprising that it's Juan Cole (thanks to Norm for the link).

Cole attacks the idea that many Americans (and the likes of Le Pen here in France) have about the Frenchness, or lack thereof, of the rioters, which can be seen in Mark Steyn's idiotic piece about the "Eurabian civil war" in the Chicago Sun-Times. Steyn complains about the media's use of the term "French youth":

"French youths," huh? You mean Pierre and Jacques and Marcel and Alphonse? Granted that most of the "youths" are technically citizens of the French Republic, it doesn't take much time in les banlieus of Paris to discover that the rioters do not think of their primary identity as "French": They're young men from North Africa growing ever more estranged from the broader community with each passing year and wedded ever more intensely to an assertive Muslim identity more implacable than anything you're likely to find in the Middle East. After four somnolent years, it turns out finally that there really is an explosive "Arab street," but it's in Clichy-sous-Bois.Cole sees this for what it is: the same sort of bullshit that has fueled the racism that's largely responsible for the situation in the first place:

The French youth who are burning automobiles are as French as Jennifer Lopez and Christopher Walken are American. Perhaps the Steyns came before the Revolutionary War, but a very large number of us have not. The US brings 10 million immigrants every decade and one in 10 Americans is now foreign-born. Their children, born and bred here, have never known another home. All US citizens are Americans, including the present governor of California. "The immigrant" is always a political category. Proud Californio families (think "Zorro") who can trace themselves back to the 18th century Spanish empire in California are often coded as "Mexican immigrants" by "white" Californians whose parents were Okies.It is refreshing to see such a piece come out of the US, instead of the ignorant chest-beating xenophobia and uninformed rhetoric of the lieks of Steyn.

In other news, Sarkozy has made the obviously asinine decision to ask for the immediate deportation of any foreigners, legal or illegal, found guilty of participating in the riots:

When one has the honor of having a titre de séjour [a visa that lasts anywhere from 1-10 years], the least we can say is that one should not get arrested provoking urban violence.While this sort of macho rhetoric might work for the "France for the French" fools (who will probably vote for Le Pen in 2007 anyway), it certainly isn't likely to help stop the rioting any time soon. If anything, it will only make the situation even worse, if that's possible.

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Popular emotion

After another night of rioting, which has spread to cities all over France and even to Belgium and Germany, and as the government is implementing a state of emergency and a curfew , it is important to take a serious look at the incidents instead of listening to news outlets that can't get their geography right or those who are calling this the intifada in France based on a two hour layover at the Charles de Gaulle airport.

First of all, Paris is not burning. Certain suburbs throughout the country are at night, but if I didn't read the newspaper or listen to the radio, I wouldn't even know that there were any riots, because, for the most part, nothing has changed in the actual city limits of Paris.

Second, this is not a religious conflict. This is a socio-economic and a racial problem, much like the LA riots in 1992 (58 dead) and the Watts riots in 1965 (32 dead). Neither is it a question of one country occupying another, so the parallels of the Palestinian intifada are ludicrous at best.

The events of the last 11 nights are complicated and seemingly contradictory, but no more so than any other instance of collective violence: there is no real ideological underpinning, but the riots are more than just senseless violence; people are angry at a country that has provided poorly for them and put up barriers against their pursuit of happiness, so they burn their own neighborhoods; the state will punish those it catches in acts of lawlessness, but its attention has been grabbed in a way that peaceful protests and letter writing campaigns have not been able to accomplish.

Robert Darnton wrote an article called Reading a riot in the New York Review of Books shortly after the LA riots, in which he discussed a book about the Paris riots of 1750.

Despite their obvious differences, one can pick out plenty of similarities between Los Angeles in 1992 and Paris in 1750: the previous histories of rioting, the settings of poverty, the influx of immigration, the prevalence of homelessness, the influence of gangs, the resentment of oppression, and the provocation of police, who made a show of force and then, with the threat of confrontation, withdrew. If George Bush will not do as Louis XV, Daryl Gates would make a credible Berryer. And the folklore of the blood bath is no more extravagant than the myth about AIDS as an epidemic unleashed by whites to destroy blacks.Likewise in Paris today, there are parallels to be seen. Nicolas Sarkozy, the current French Minister of the Interior, would probably empathize with Gates and Berryer (the chiefs of police in Los Angeles in 1992 and Paris in 1750, respectively). But we must be careful about blindly applying one historical event upon another similar one, and avoid at all costs forcing two dissimilar ones together to suit an ideology or a strained narrative, like so many American bloggers seem intent on doing with their imaginary clash of civilizations.

But even if they run parallel, the comparisons do not lead anywhere, because the past does not provide pre-packaged lessons for the present. The rioters of Paris inhabited a mental world that differed completely from that of the rioters in Los Angeles; and the history of rioting demonstrates the need to understand mentalités in all their specificity rather than to search for general models. Riots have meanings as well as causes. To discover what they mean, we must learn to read them, scanning across centuries for patterns of behavior and looking for order in the apparent anarchy that explodes under our noses. We have a long way to go; but if we ever get there, we may be able to make sense of what has seemed to be the most irrational ingredient of our civilization: "popular emotion."

The problem here is a complex one, and it has no easy solutions. Second and third generation children of immigrants from Africa and Asia have not been integrated into French society, and many opportunities remain out of their reach, due to a vicious cycle of a lack of governmental integration efforts and communautarisme or ghettoization. At this point, it's not really important which came first; they both feed on each other. This is illustrated in a lack of representation of a group of people that is French and makes up around 12% of France's population. There are very few minority politicians and, besides comics and rappers, I can only think of one Arab who is regularly on television: Rachid Arhab, who is often referred to as Rachid l'Arabe.

France, like many other countries, has not done a good job of integrating the immigrants who were necessary for the country's development and their French children. And in order to prevent things like this from happening again, it's going to take more than quick fixes and band-aids. But in the end, that's the problem: no one pays attention to these people until it's too late; no one talks very seriously about reforming state housing, fighting against discrimination, bettering education and raising employment in these areas until they're already ablaze.

So while the electrocution of the two boys in Clichy-sous-Bois and Sarkozy's televised comments about taking out the trash probably ignited the riots, the fuel for them has been laying around dormant for a while.

In his article about the incidents in Aulnay-sous-Bois, Alex Duval Smith of The Observer quotes a youth of Algerian descent whose opinions are lucid and, unfortunately have a certain logic about them:

'He [Sarkozy] should go and fuck himself,' says HB, who was born in France of Algerian parents. 'We are not germs. He said he wants to clean us up. He called us louts. He provoked us on television. He should have said sorry for showing us disrespect, but now it is too late.'

HB's views are clear. 'The only way to get the police here is to set fire to something. The fire brigade does not come here without the police, and the police are Sarkozy's men so they are the ones we want to see.'

All the dustbins were burnt long ago. 'Cars make good barricades and they burn nicely, and the cameras like them. How else are we going to get our message across to Sarkozy? It is not as if people like us can just turn up at his office.' ...

Jobs? 'There are a few at the airport and at the Citroën plant, but it's not even worth trying if your name is Mohamed or Abdelaoui.' ...

When asked if he considers himself integrated in France, HB claims that is not his aspiration. 'I am not sure what the word means. I am part of Mille-Mille and Seine-Saint-Denis, but I am not part of Sarkozy's France, or even the France of our local mayor whom we never see. At the same time, I realise I am French, because when I visit my parents' village in Algeria that doesn't feel like home either.'

Monday, November 07, 2005

The religious conflict that isn't

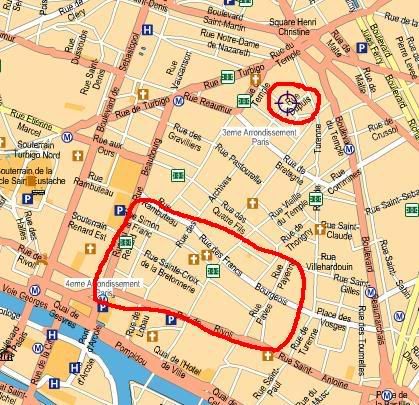

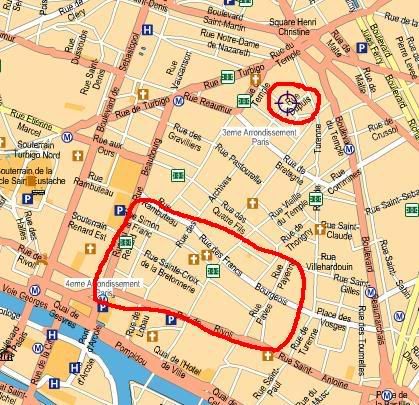

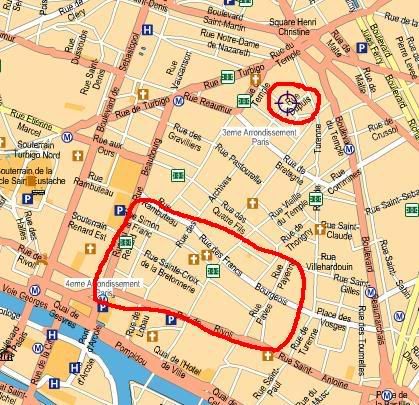

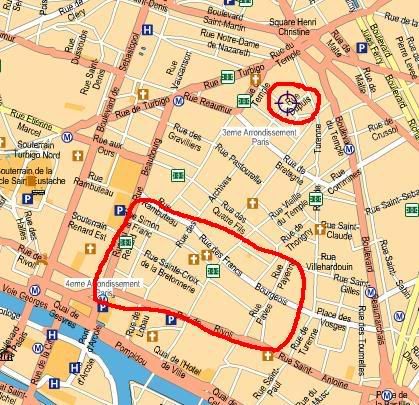

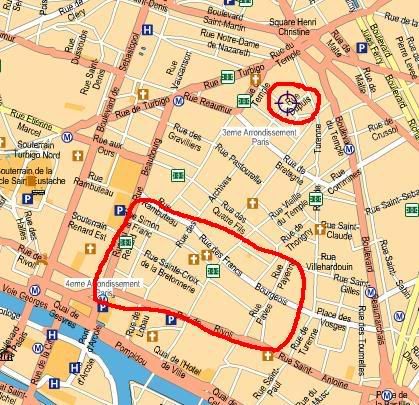

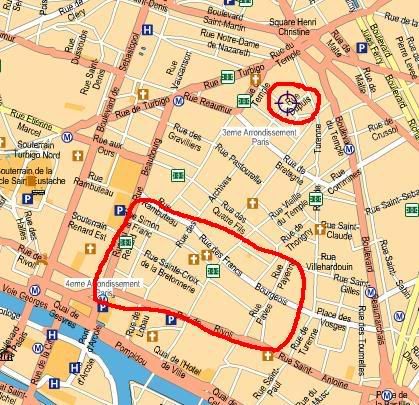

Today's Times includes a very misleading account of the riots in the Parisian region. It says that rue Dupuis, where some cars were burned Saturday night, is in the Marais and makes a point of saying that it is the old Jewish district:

On Sunday, a gaping hole exposed a charred wooden staircase of a smoke-blackened building in the historic Marais district of Paris, where a car was set ablaze the previous night. Florent Besnard, 24, said he and a friend had just turned into the quiet Rue Dupuis when they were passed by two running youths. Within seconds, a car farther up the street was engulfed in flames, its windows popping and tires exploding as the fire spread to the building and surrounding vehicles.A quick look at a map of Paris, however, shows that rue Dupuis is not in the Marais; it is very close to Place de la République and is in the 3rd arrondissement, whereas the Marais is mostly in the 4th by the métro station St. Paul:

"I think it's going to continue," said Mr. Besnard, who is unemployed.

The attack angered people in the neighborhood, which includes the old Jewish quarter and is still a center of Jewish life in the city. "We escaped from Romania with nothing and came here and worked our fingers to the bone and never asked for anything, never complained," said Liliane Zump, a woman in her 70's, shaking with fury on the street outside the scarred building.

When the Times incorrectly insinuates that Paris's historically Jewish neighborhood, which is coincidently its homosexual neighborhood as well, has been targeted by rioters, their mistake gives a purely social problem a false air of religious conflict. But I suppose sensationalism sells.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Sunday, November 27, 2005

Sleepless in Sudan

Via Kristof's column today, I found a blog by an aid worker in Darfur, who is giving uncensored information from Sudan and who, for fear of being kicked out of the country, is remaining anonymous.

In case you can't access the Kristof article, he's not really saying anything new: the African Union peacekeepers don't have enough people, money or matériel; the US isn't doing anything; things are getting worse, not better.

But at least Kristof keeps writing about Darfur. He may, at times, sound like a slightly annoying record that keeps skipping, particularly if you listen to the multimedia pieces on the Times website, but he is one of the only people from a large American media outlet who has been struggling to keep Darfur ingrained in his public's fickle short-term memory. And for that, he deserves respect.

Saturday, November 26, 2005

Rigged Guantanamo Bay military commissions

I just received a package from my family with some Christmas presents and the last three months of Harper's. There was a "reading" in there that I had never heard about. It is an exerpt from a March 2004 email in which Air Force Captain John Carr, one of the military prosecuters in the cases at Guantanamo Bay who has since then been transferred, complained to Army Colonel Fred Borch about the way the Office of Military Commissions was being carried out.

The Australian Broadcast Service seems to be the first to report that the trials were to be rigged.

I can't seem to find a transcript of the email on the internet, so I'm retyping the exerpt published in the November issue of Harper's (emphasis mine):

Sir,According to the ABC article, prosecutor Major Robert Preston feels the same way: "After all, writing a motion saying that the process will be full and fair when you don't really believe it is kind of hard, particularly when you want to call yourself an officer and lawyer."

I feel a responsibility to emphasize a few issues. Our cases are not even close to being adequately investigated or prepared for trial. There are many reasons why we find ourselves in this unfortunate position--the starkest being that we have had little or no leadership or direction for the last eight months. It appears that instead of pausing, conducting an honest appraisal of our current preparation plan for the future, we have invested substantial time and effort in concealing our deficiencies and misleading not only each other but also those outside our office who are either directly responsible for or asked to endorse our efforts. My fears are not insignificant that the inadequate preparation of the cases and misrepresentation related thereto may constitute dereliction of duty, false official statements, and other criminal conduct.

You asked in our meeting last week what else you could do but lead by example. In regards to the environment of secrecy, deceit, and dishonesty in this office, the attorneys appear merely to be following the example that you have set.

A few examples include:

You continue to make statements to the office that you admit in private are not true. You have stated for months that we are ready to go immediately with the first four cases. At the same time, emails are being sent out admitting that we don't have the evidence to prove the general conspiracy, let alone the specific accused's culpability.

You have repeatedly said to the office that the military panel will be handpicked and will not acquit these detainees, and we only needed to worry about building a record for the review panel. In private you stated that we are really concerned with review by academicians ten years from now, who will go back and pick the cases apart.

The fact that we did not approach the FBI for assistance prior to December 17 is not only indefensible but an example of how this office and others have misled outsiders by pretending that interagency cooperation has been alive and well for some time, when in fact the opposite is true.

It is my opinion that the primary objective of the office has been the advancement of the process for personal motivations--not the proper preparation of cases or the interests of the American people. The posturing of our prosecution team chiefs to maneuver onto the first case is overshadowed only by the zeal with which they hide the specific facts of their case from review or scrutiny. The evidence does not indicate that our military and civilian leaders have been accurately informed of the state of our preparation, the true culpability of our accused, or the sustainability of our efforts.

If the appropriate decision-makers are provided with the accurate information and determine that we must go forward on our current path, then all would be very committed to accomplishing this task. It instead appears, however, that the decision-makers are being provided false information to get them to make the key decisions, only to learn the truth after a point of no return.

When I volunteered to assist with this process, I expected there would at least be a minimal effort to establish a fair process and diligently prepare cases against significant accused. Instead, I find a half-hearted and disorganized effort by a skeleton group of relatively inexperienced attorneys to prosecute fairly low-level accused in a process that appears to be rigged. It is difficult to believe that the White House has approved this situation, and I fully expect that one day, soon, someone will be called to answer for what our office has been doing for the last fourteen months.

While many may simply be concerned with a moment of fame and the ability in the future to engage in small-time practice, that is neither what I aspire to do not what I have been trained to do. I cannot morally, ethically, or professionally continue to be a part of this process.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Padilla's indictment

Jose Padilla, an American citizen, was finally indicted yesterday in a criminal court. Padilla, who has been held as an "unlawful enemy combatant" in a Navy brig in South Carolina since 2002, was arrested in Chicago and accused of planning a "dirty bomb" attack on American soil. His indictment makes no mention of a "dirty bomb," perhaps because any evidence gained while he was detained without recourse to a writ of habeas corpus would be inadmissable in court.

According to I. Michael Greenberger, a former Justice Department official who teaches law at the University of Maryland,

The indictment is doubtless a strategy by the Bush administration to avoid a Supreme Court ruling that would likely hold that U.S. citizens cannot be detained incommunicado as enemy combatants if they are detained on U.S. soil.The US government had until today to turn in its legal arguments for a pending Supreme Court case, which was to examine Padilla's status. Attorney General Gonzales claims, "Since he has now been charged in a grand jury in Florida, we believe that the petition is moot and that the petition should not be granted." But this is not at all certain, since the change to the US criminal court system did not address his status as an "unlawful enemy combatant," (a designation that is being used to hold other people indefinitely) and in a government request in 2002 to suspend a petition to habeas corpus, government lawyers make the following claim in a footnote:

There has never been an obligation under the laws and customs of war to charge an enemy combatant with an offense (whether under the laws of war or under domestic law). Indeed, in the usual case, the vast majority of those seized in war are never charged with an offense but are simply detained during the conflict. Nor is there any general right of access to counsel for enemy combatants under the laws and customs of war.This implies that the government is talking about the "war on terror" and not the war in Afghanistan, because if they were talking about the latter, Padilla would have been released before now. Needless to say, this is disconcerting, because if the "war on terror" were to last as long as another metaphorical war, say the "war on drugs," the "unlawful enemy combatant" designation would give the president the power to imprison anyone, even US citizens, for the rest of their lives without having to ever charge them with a crime.

As a matter of fact, the Supreme Court decision handed down by O'Conner in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (Hamdi is an American citizen who was apprehended in Afghanistan during the war there) explicitly makes this point:

Hamdi objects, nevertheless, that Congress has not authorized the indefinite detention to which he is now subject. The Government responds that "the detention of enemy combatants during World War II was just as 'indefinite' while that war was being fought." Id., at 16. We take Hamdi's objection to be not to the lack of certainty regarding the date on which the conflict will end, but to the substantial prospect of perpetual detention. We recognize that the national security underpinnings of the "war on terror," although crucially important, are broad and malleable. As the Government concedes, "given its unconventional nature, the current conflict is unlikely to end with a formal cease-fire agreement." Ibid. The prospect Hamdi raises is therefore not far-fetched. If the Government does not consider this unconventional war won for two generations, and if it maintains during that time that Hamdi might, if released, rejoin forces fighting against the United States, then the position it has taken throughout the litigation of this case suggests that Hamdi's detention could last for the rest of his life.O'Conner then goes on to speak of the "constitutional balance" needed when weighing freedom and security:

Striking the proper constitutional balance here is of great importance to the Nation during this period of ongoing combat. But it is equally vital that our calculus not give short shrift to the values that this country holds dear or to the privilege that is American citizenship. It is during our most challenging and uncertain moments that our Nation's commitment to due process is most severely tested; and it is in those times that we must preserve our commitment at home to the principles for which we fight abroad. See Kennedy v. Mendoza&nbhyph;Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 164?165 (1963) ("The imperative necessity for safeguarding these rights to procedural due process under the gravest of emergencies has existed throughout our constitutional history, for it is then, under the pressing exigencies of crisis, that there is the greatest temptation to dispense with guarantees which, it is feared, will inhibit government action"); see also United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258, 264 (1967) ("It would indeed be ironic if, in the name of national defense, we would sanction the subversion of one of those liberties ... which makes the defense of the Nation worthwhile").I've talked about this idea on a few occasions (here and here), and the prospect of an executive branch that has the power to indefinitely detain its citizens is indeed a frightening one. This is why it is important that the Supreme Court go ahead and hear the case, instead of letting the government cop out at the last minute. This is not unexpected, however, since rather than actually try Hamdi, the government agreed to let him go back to Saudi Arabia on the condition that he give up his American nationality.

So the government's behavior in both of these cases is not only unconstitutional and contrary to the tule of law in general, it seems contradictory and counterproductive. If Padilla was really trying to build a "dirty bomb," the prosecuter in his case cannot make that claim due to his unlawful detention. Likewise, if Hamdi is so dangerous, why let him go back to Saudi Arabia (of all places!) rather than give him a fair criminal trial? It's important that the Supreme Court hear Padilla's case regardless of the government's last minute cop-out, if only to stress Justice O'Connor's assertion that "...a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation's citizens."

Monday, November 21, 2005

The Salvador option

Last night, I began reading Mark Danner's book, The Massacre at El Mozote , which descibes the brutal murder of hundreds of people in a sacristy in a small Salvadoran village by American-backed government forces fighting a dirty war against leftist rebels. As coincidence would have it, I saw (via Christopher Dickey's blog) that the Salvadoran former colonel, Nicolas Carranza, had been found responsible for crimes against humanity in a court in Memphis. Carranza, who moved to Memphis in 1985 and then became an American citizen, was the Vice Minister of Defense in El Salvador from 1979 to 1981 and then head of the Treasury Police in 1983. The latter was reputed to be the most violent of the country's security forces.

For more information on the Salvadoran civil war, see the report by the Truth Commission.

The massacre in El Mozote is interesting to me in and of itself, but it does have some relevance to the situation in Iraq. Earlier this year, Christopher Dickey briefly explored the prospect of employing the "Salvador Option" in Iraq. Presumably, these dirty war tactics would entail not only assassination and kidnapping, but also torture. The recent discovery of the Iraqi Interior Ministry's secret interrogation center -- where many Sunnis were apparently tortured, perhaps by members of the Shia paramilitary forces of the Sadr Brigade, who have reportedly become deeply embedded in the Ministry -- should bring up questions about torture carried out by the US and its allies in Iraq.

We have known for a long time what US proxy forces did in Central America, so why should we be suprised when the same thing happens in Iraq, particularly since the Bush administration was reported to have been debating the "Salvador option" only 10 months ago?

In any case, those who are committing torture in Iraq, be they American or Iraqi, should take note of Carranza's trial, because, as Hissène Habré and Joseph Kony will find out soon enough, they are not above the law.

On standing down

Last week, Vietnam veteran and Pennsylvania Congressman Murtha, who is the ranking member of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense, gave a speech in which he outlined the reasoning behind his proposed motion to redeploy all American forces out of Iraq "at the earliest praticable date..." maintaining "a quick-reaction U.S. force and an over-the-horizon presence of U.S. Marines...in the region."

The reasons he gives, which are stated in his proposal, are as follows:

...Congress and the American People have not been shown clear, measurable progress toward establishment of stable and improving security in Iraq or of a stable and improving economy in Iraq, both of which are essential to "promote the emergence of a democratic government";I won't even go into the Republican response to his motion, which was childish and counterproductive, but probably smart politics; however, Murtha's reasoning deserves to be looked at honestly.

...additional stabilization in Iraq by U, S. military forces cannot be achieved without the deployment of hundreds of thousands of additional U S. troops, which in turn cannot be achieved without a military draft;

...more than $277 billion has been appropriated by the United States Congress to prosecute U.S. military action in Iraq and Afghanistan;

...as of the drafting of this resolution, 2,079 U.S. troops have been killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom;

...U.S. forces have become the target of the insurgency,

...according to recent polls, over 80% of the Iraqi people want U.S. forces out of Iraq;

...polls also indicate that 45% of the Iraqi people feel that the attacks on U.S. forces are justified;

...due to the foregoing, Congress finds it evident that continuing U.S. military action in Iraq is not in the best interests of the United States of America, the people of Iraq, or the Persian Gulf Region, which were cited in Public Law 107-243 as justification for undertaking such action;

It has long been argued that a premature withdrawal of American troops would lead to an all out civil war in Iraq. It is hard to say, however, how accurate this idea is. It is entirely possible that the only thing holding the Iraqi people together is a common enemy: the Americans. (I am immediately reminded of the Syrian forces that stopped the war in Lebanon and then subsequently occupied the country for a decade and a half, as well as the comment made to me by a Palestinian born and raised in Lebanon, who said she hoped the Syrians wouls stay, because she didn't want another civil war to break out.) However, there is also the distinct possibility that Murtha is correct and US forces are the destabilizing force in the region. If there were no coalition forces to resist, there would be no need for a nationalist Iraqi insurgency, and those who continued to fight the Iraqi government would be seen as sectarian belligerents or religious zealots instead of nationalist freedom fighters.

But I'm not really sure that that's the real question we should be looking at. The important question is that of security versus democracy. If what we are really interested in is Iraqi stability, then we should have left Saddam Hussein in charge. But we purport to be interested in more than just security; the post-invasion rhetoric has been largely about liberating Iraqis and fostering democracy in the Middle East. Granted, there is a certain moral responsiblity inherent in the pottery barn motto of "you break it, you bought it," which would suggest that we have an obligation to clean up the mess we made. But there comes a time when even if it is our fault, we have to ask ourselves if we are only making matters worse by trying to clean up our mess.

And besides, to go back to the idea of democracy, if Iraq is, in fact, a sovereign nation, that decision is not really ours to make in the first place. To my mind, there ought to be a national referendum during the December elections that asks each Iraqi voter, "should the coalition forces withdraw from Iraq?" If the answer is "yes," then we should respect the Iraqi people's wishes and withdraw as soon as possible. However, we should still offer to train Iraqi police and military forces in addition to teachers, engineers, and anyone else needed to help rebuild Iraq's demolished infrastructure. This could be in somewhere like Kuwait or Qatar.

In the end, perhaps we should stand down, so the Iraqis can stand up.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Guantanamo Bay and habeas corpus

In order to understand the motions to be voted on later today about habeas corpus rights for detainees at Guantanamo Bay, it is useful to step back, with the help of Human Rights Watch's overview, and review the whole process in motion there.

President Bush declared in November 2001 that non-US citizens accused of terrorism could be tried by an ad-hoc military commission, instead of by a court martial or a federal civilian court. The justification was that the people being detained were not prisoners of war, but rather "enemy combatants," who have no rights under the Geneva Conventions. There are about 550 people being detained at Guantanamo Bay, detained sometimes by US forces, sometimes by foreign services or turned over to the US by the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan in exchange for a $5,000 bounty. Some have been released, mostly because of deals with their home governments, who have expressed dissatisfaction with the proposed ad-hoc military commissions. The British Attorny-General described them as "not ... the type of process which we would afford British nationals."

The purpose of military commissions is to try non-US citizens who are charged with having participated in international terrorism against the United States. Authorized in November 2001, their panels are made up of 3-7 members, all of whom must be current or retired members of the US military and only one of which must have a law degree. The detainee must be assigned military defense council, but can hire a civilian lawyer at his own expense. According to HRW,

The normal rules of procedure in a court martial do not apply in the military commissions. Hearsay evidence can be admissible. Decisions are based on a majority of commission members, except in death penalty cases, where a unanimous verdict is required. Cases are reviewed by a military review panel, but there is no appeal to a civilian court as is the case with courts martial. Final review rests with either the Secretary of Defense or the President.To date, only 4 detainees have been formally charged with offences in odrer to be tried in a military commission.

In the meantime, while many detainees will begin their 5th year of detention at Guantanamo Bay this year, the Department of Defense has set up these tribunals for detainees to challenge their status as a "enemy combatants." They were introduced in response to the supreme court decision in Rasul v. Bush, in which the Court ruled that federal courts had the jurisdiction to hear claims made by Guantanamo detainees challenging their imprisonment.

Each detainee is assigned a "personal representative," who is a military officer and not a lawyer, to assist him in the process. He then appears before 3 military officers, who decide whether or not he has been correctly labeled as an "enemy combatant."

According to the Washington Post, the DOD has stated that 558 Tribunals have taken place. Of these, the tribunal have decided on 509 cases, of which 33 detainees were found not to be "enemy combatants," but only 4 have been released. The same article, takes a look at the first case in which classified evidence used in the tribunal has become public.